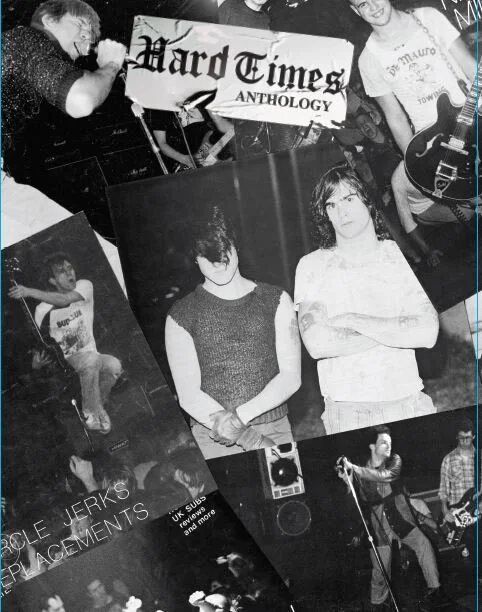

Hard Times

The following is an excerpt from Hard Times Magazine: An Anthology of ‘80s Punk & Hardcore by Ron Gregorio and Amy Yates Wuelfing

In preparing the Hard Times anthology book, author and publisher Ron Gregorio spoke to old friend Lyle Preslar about the early days of punk ‘zine culture.

Lyle Preslar, as told to Ron Gregorio

“I’ve been occasionally a guest on the SiriusXM shows, so I’m around these music journalists who used to work for Rolling Stone, and they talk to me like, “Oh yeah, yeah, Minor Threat, you were great…” and I’m thinking, You motherfuckers wouldn’t have been caught dead at one of our shows or even sent anyone you know, so don’t try to pretend to me now 30 years later… Back then you couldn’t care less about us and there were other people that did care.

My point about fanzines, because, let’s face it, even college radio was very limited… they played the music, but they rarely interviewed the bands or had any information about the bands. Even when they played the music it was pretty limited in time and geography. It was just a few people listening who happened to be able to get the radio signal. Maybe in a big city like New York, or LA, or Chicago, you’d get a few hundred listeners, so if a fanzine was distributing a few hundred copies that was important for the bands. You relied on fanzines to try to deliver some information, but the problem was that you had no idea how accurate it was or how old it was. By the time you got a copy of that fanzine it could have been six months old.

‘Zines gave you the ability to get a window on a scene that you had no idea about. People find it hard to believe, but back in the 1980s we knew there was a place called LA and San Francisco, and there were bands playing in these places, we just had no idea where they were or what these clubs and neighborhoods looked like. In some cases, we would just show up in these cities and hook up with these people based only on information we got from fanzines. We would roll up, and there they’d be, and we would know who they were because of some pictures in a fanzine. It made every trip this incredible discovery because you really didn’t know what you would find. It was great fun and it always seemed like you were doing something interesting, unlike now, where you have so much information. We never stayed in hotels, we would just stay with other bands and their friends. A lot of the time we would just sleep on the floor. Part of it was because we had no money, but a bigger part of it was that was the idea. We wanted to be part of their scene, and when they came out to our town, they would stay with us.

The initial contact that we had with Black Flag was when they came to town and needed a place to stay, so they stayed with Ian. This was before Henry [Rollins joined Black Flag] when Henry was just some guy in D.C. We eventually went to LA and we stayed at SST [Records office], and almost every bit of information we had about them before that was what we read in fanzines. Some of it was wildly inaccurate, but it was [so] interesting that you didn’t really care whether the person producing or writing a fanzine was an authority. It was more about what information did it have, or appear to have? So, if it was thick and fancy with a lot of writing, like Flipside, you would think, Ok, these guys really know what’s going on. And, if it didn’t, you wouldn’t take it as seriously. This wasn’t necessarily an accurate assessment, but we had nothing to compare it to.

Through fanzines, you got a window on these places and people that, in many cases, you have never met, and you might never meet, or [you might] never even get to see their band play. Because you had no other sources, you would read an interview in a fanzine and form opinions of what these people were really like. And then you would meet them and think, wow that’s what they’re really like! Sometimes you’d find out that someone was really funny, but that never came across in an interview. Or, you’d find out that they’re so much more considerate. When we went to Los Angeles we hung out with Black Flag and we though Black Flag was “the LA scene.” But it was more like a contingent. We were a part of the Black Flag contingent, and then, all of a sudden, I’m being told: “Well, the Bad Religion people are a different scene.” Some of these guys were so angry with each other and I don’t understand why. It was almost like street gangs, essentially, and fanzines were often the sources of this strife.

The first time we went out to LA there was a cartoon in a fanzine that was a very negative depiction of TSOL. Somehow or another, the guys in TSOL got the mistaken impression that [Minor Threat guitarist] Brian Baker was the guy who did the cartoon. He had nothing to do with it, it was another Brian. We’re at this big show and there were several different factions there, and these guys come at us. TSOL are huge, they’re all six feet or bigger, and they grab Brian and say, “We’re going to kill you.” It took us, like, 20 minutes to convince them that Brain Baker was not the Brian that drew the pictures. And the funny thing about it was that it was a fanzine that came out of Michigan. We’re from DC, TSOL is from LA, the fanzine is from MI, and, somehow, they’re all coming together in this potentially violent situation. Once we convinced them of that, we became friends, which was weird because we had nothing in common with them.

Fanzines can’t exist now because of the internet. Blogs. There’s no clubs and only a few bands coming through the way we did. Now you put yourself on YouTube and hope somebody sees it, but how do you stand out? There’s no club scene to build a fanbase and there’s no word of mouth. We had groups of kids who would see shows and then hang out together and talk about the shows we saw, and that’s how bands grew a fanbase. I don’t know how anyone could do it now.

– Lyle Preslar